Mohamed Zaree receives Martin Ennals prize.

Read it here

Author: issandr

La structure tribale en Libye : facteur de fragmentation ou de cohésion ? – Fondation pour la recherche stratégique

Mohamed Ben Lamma.

http://ift.tt/2y9Ks3t

The Farce Behind Morsi’s Death Sentence – The New Yorker

Jon Lee Anderson:

As its leaders present and former grapple with their legacies, Egypt, no longer a regional leader of any sort, is mired in a miasma of self-made miseries, a nation best known for its corruption, poverty, and the absence of the rule of law. The 2011 “revolution” that seemed to have pulled it briefly from its steadfast implosion seems not only to have come and gone but to have been a mirage.

Tragically, Cairo’s Tahrir Square is likely to be remembered as a place where hopes were raised for democratic change, only to have those hopes dashed by the country’s perennial powers-that-be. The decision by Egypt’s judiciary to kill Morsi is not only a crudely cartoonish attempt at the implementation of justice; it defies even the kind of canny political logic that one might expect from a military élite like Egypt’s. If Egypt’s generals thought that brutality would buy them control, they didn’t get it. In the Sinai, ISIS now runs amok, seizing police posts and massacring captives. As for the heroes of the country’s Arab Spring, so vaunted by the West during that fateful spring of 2011, most have left the country, been killed, or are themselves in prison. The farcical show trials, in which Morsi and other former senior officials are exhibited in courtrooms in cages, covered with soundproofed glass so that they cannot be heard shouting, must be seen for what they are, alongside a myriad of arbitrary arrests and detentions, including of journalists.

Reporting on Yemen

A Yemeni reporter for the Washington Post talks about a war that is not too close for comfort:

Increasingly, Sanaa is turning into a ghost town. The universities, once bustling with students, have closed. So, too, have many businesses. People are packing their belongings into their pickup trucks and sedans and driving to far-away villages, hoping to avoid the air raids that have turned the mountains surrounding Sanaa into fiery-orange volcanoes.

The campaign, with a coalition of Arab nations, is an effort to dislodge Houthi rebels sweeping through Yemen.

The evenings are what alarm me most. That’s when the bombings intensify.

With Sanaa increasingly deprived of electricity, the lack of lighting creates an eerie darkness that is punctuated by the flashes — and explosions that quickly follow — that briefly illuminate my home town.

I’m also increasingly away from my wife. I’ve moved her family into our home because of the air raids. To make room, I’ve been staying at my father’s house, which is across town. I think that the family is safer this way, but all I want is to be home with my wife.

I spend my evenings trying to sleep, but often I can’t. I think about how I’ll report on the following day’s events. Will the Houthis capture the southern port city of Aden? I then inevitably ponder my own mortality. Will my family be killed in the attacks? Will I wake in the morning?

The Humble Tomato | MERIP

A fun riff on the tomato in Egyptian political culture by Tessa Farmer:

A common joke uses tomato sauce as a reference point for the country’s political difficulties as well. “Law nahr al-Nil ba’a salsa, mish haykaffi al-kusa illi fiki ya Masr (Even if the Nile became tomato sauce, it wouldn’t be enough for all the zucchini in Egypt).” Zucchini, or kusa, is often made into mahshi, stuffed with rice and cooked in tomato sauce, a popular meal for those who work hard to stretch their food budgets. Kusa is also a gloss for nepotism and corruption, the joke being that the problem is so endemic that a river of tomato sauce could not cover it up.

Over the last several years, tomatoes have frequently figured as mediums of Egyptian political sentiment as one dynasty folded and others struggle to be born. There was the kerfuffle in 2012 over a Facebook post by a salafi group warning that the tomato is a Christian fruit because, when cut in half, its insides resemble a cross. It was another nail in the coffin of rational thought among the religiously oriented, or so argued those opposed to the rise of the Muslim Brothers and other religious parties. “These people,” it was said, even cast sectarian aspersions on the prosaic tomato! Then there were the rumors that Israeli tomatoes in the Egyptian market were poisoned with high concentrations of solanine, a naturally occurring glycoalkaloid in plants in the nightshade family. The story started, it seems, with the idea that genetically modified seeds from Israel were being smuggled in through Gaza. Last, but certainly not least, were the tomatoes and shoes thrown at Secretary of State Hillary Clinton during her summer 2012 visit to Egypt by people who blamed the US for supporting the Muslim Brothers during their short and contentious time in power. Clinton brushed aside the intentions behind those tomatoes and instead lamented the waste of food. The humble tomato sure gets around.

Partisan leader: President is not interested in parliament elections

Via Egypt Independent, striking quotes (for him) from Social Democratic Party leader Mohammed Aboul Ghar on the (yet again) postponement of parliamentary elections in Egypt because a the Supreme Constitutional Court found the electoral district law to be unconstitutional. Aboul Ghar was an important cheerleader for Abdelfattah al-Sisi’s coup in July 2013, only find his party and others like it sidelined by an electoral setup that favors a fragmented parliament with small electoral district to favor local notables and vote-buying (both tend to be more difficult/expensive in larger districts, where it is more helpful to have a party machine to organize) with strong control by the presidency. Many will say it’s too little too late for a system that has gone from (allegedly) “one man, one vote, one time” to “one man (Sisi), all the time, no vote”, but considering Aboul Ghar and his ilk have been largely to cowed by the return of the security state to express even a semi-coherent political discourse, this should be welcomed. After all, if no one is asking for anything better, it’s hardly likely to come.

A renowned politician has said that President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi does not want parliamentary elections to be held at the current period, days after a verdict was handed down by the Supreme Constitutional Court against the constitutionality of the law regulating the polls, causing its postponement.

“The president does not want a parliament right now, hence the delay in the official invitation for voting and the large number of unconstitutional legislations adopted by the state in the absence of the parliament,” said Mohamed Abul Ghar, chairman of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, adding that many laws enacted over the past period turn Egypt into “a police state”.

“The general atmosphere suggests that the president and the state either do not want a parliament at all, or seek a fragile, divided parliament that is unable to make a decision or practice oversight on the executive authority.”

Abul Ghar, however, said that the court’s verdict against the constituencies law has nothing to do with the regime’s disinterest in elections.

“The court ruling, in my judgement, was independent and objective, addressing an unconstitutional law,” Abul Ghar said.

Asked whether the postponement of elections has any benefits, Abul Ghar replied, “If the electoral system is not changed entirely, there would be no gains, just losses, it is a futile postponement.”

A lonely fight defending Egypt’s jailed dissidents

Great profile of Egyptian lawyer Ragia Omran by the AP’s Hama Hendawi:

Defending arrested activists is Omran’s way of keeping the revolution alive.

“We are not going to accept that the police state will continue to run the country unchallenged. There have to be people who object to this, and we are going to be those people – I and the others who are with me,” she said one afternoon after a court hearing for 25 young men on trial for breaking a draconian law effectively banning protests which was adopted a year ago.

“I cannot give up. My friends and family want me to leave the country. I cannot,” she told The Associated Press in one of several recent interviews.

. . .

The 41-year-old Omran earns her living as a corporate lawyer. Defending activists is her volunteer work. That can mean punishing hours. One recent day, she attended the signing of a nearly $700 million loan deal that her firm helped work out. In the days that followed, she was in court representing jailed activists, tromping into police stations to find clients, and visiting prisons, trying to bring food and other supplies to detainees.

She often keeps clothes in her car so she can make quick changes out of her corporate business suit and heels. Her mobile gets a constant stream of texts and calls. Sometimes she herself cooks food to take to inmates – things that can go a few days without spoiling.

Standing only 5 feet tall (1.53 meters), she charges with determined steps into prisons, police stations and courtrooms, where she meets constant resistance from authorities.

“In the first two years after the revolution, police and the Interior Ministry were careful with us because they didn’t want bad publicity,” she said. “Now they don’t care… This regime does not care about its image, the law or regulations.”

Springborg: The resurgence of Arab militaries

Like the previous post also at Monkey Cage, Robert Springborg makes an interesting argument about the Arab uprisings have empowered militaries:

The Arab upheavals and reactions to them have resulted in a profound militarization of the Arab world. In the republics, this has taken the form of remilitarizing Egypt, further entrenching the power of Algeria’s military and possibly preparing the Tunisian military for an unaccustomed role in the future. In the other republics, regime supporting militaries have been pitted against militias emerging from protest movements, with both sides attracting external support. In the monarchies, ruling families have bolstered their militaries by increasing their capabilities and by roping them together in collective commands. They have done so primarily to confront and put down further upheavals, wherever in the Arab world they might occur, but probably also as part of intensifying intrafamily power struggles. Behind this militarization is the U.S. presence in various forms, including as primary supplier and trainer, operator of autonomous bases and orchestrator of counter terrorist campaigns.

This, he argues, may be particularly significant for the Arab oil-rich monarchies that are significantly beefing up the abilities of their armed forces, which Springborg says is a “double-edged sword”.

The Jews-Only State

All par for the course in “the only democracy in the Middle East” (from The Guardian):

A controversial bill that officially defines Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people has been approved by cabinet despite warnings that the move risks undermining the country’s democratic character.

Opponents, including some cabinet ministers, said the new legislation defined reserved “national rights” for Jews only and not for its minorities, and rights groups condemned it as racist.

The bill, which is intended to become part of Israel’s basic laws, would recognise Israel’s Jewish character, institutionalise Jewish law as an inspiration for legislation and delist Arabic as a second official language.

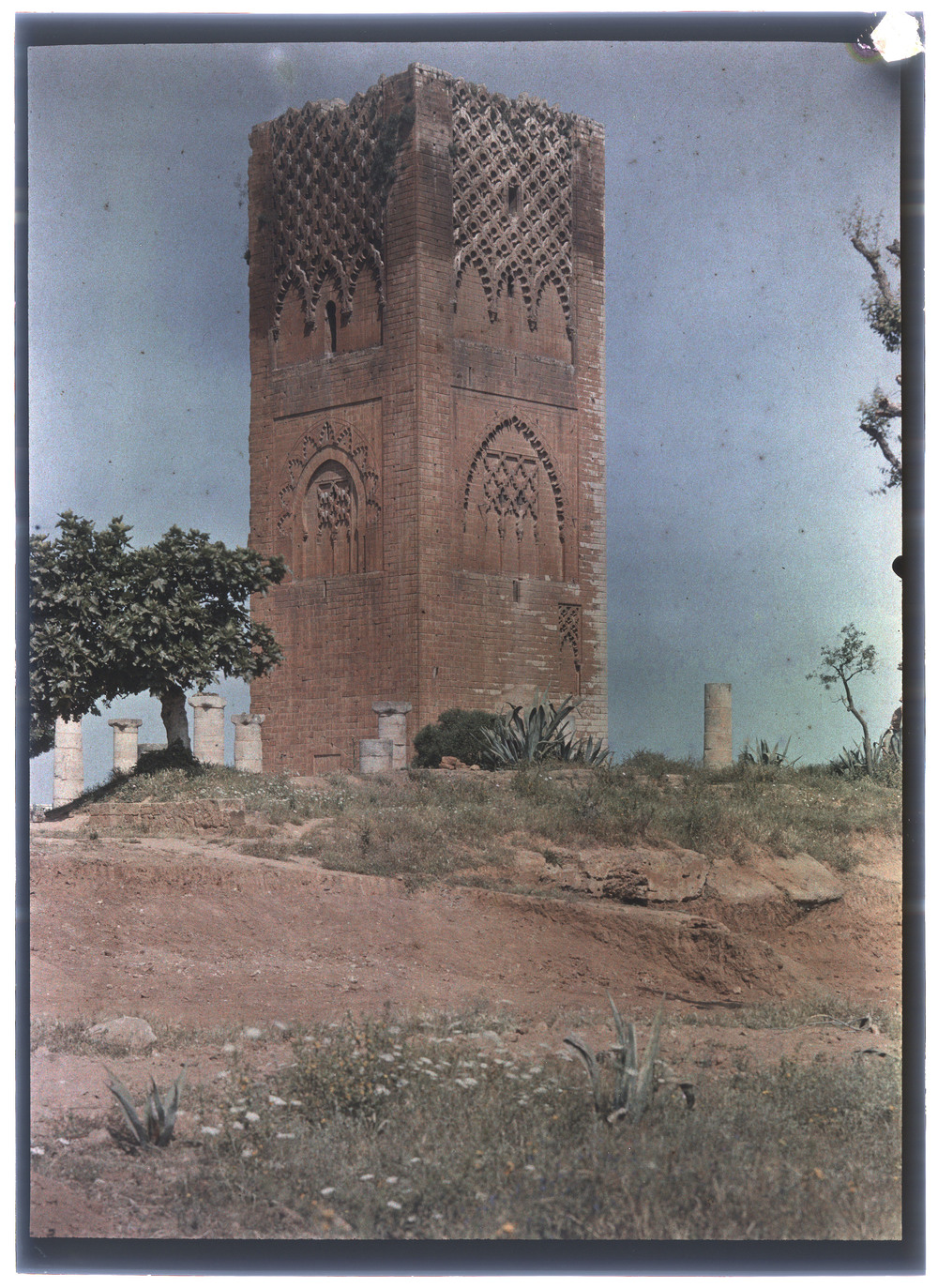

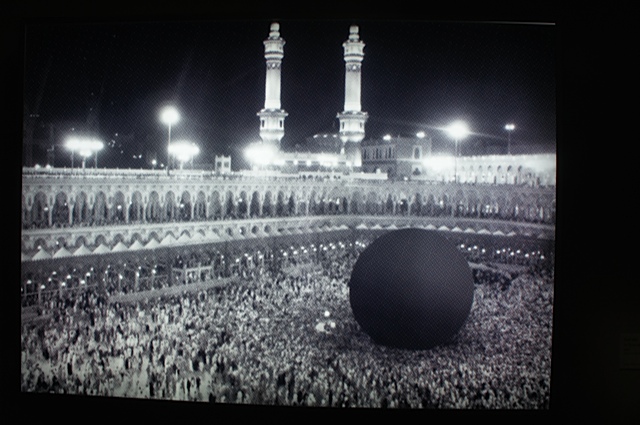

Morocco & its arts

In the last month I have somewhat serendipitously been exposed to a lot of Moroccan art. In my new hometown of Rabat, the country’s first museum of modern and contemporary art just opened. In Paris, where I was visiting last month, there are three ongoing exhibitions dedicated to Morocco.

If you can stand the line and the lobby at the Louvre, the show on medieval Morocco is well worth it, traveling through the successive dynasties that ruled Morocco (and most of Spain) from the 8th to the 15th century, founding cities such as Marrakesh, Rabat and Seville and developing arts and crafts that were imitated and prized (and stored in Church vaults) across Europe. It was the rise and fall of these Berber dynasties that inspired the Arab historian Ibn Khaldoun’s famous theories on the cyclical nature of power. The chandeliers, coins, textiles, mosaics, vases, texts, minbars and doors on display are beautiful. One does not experience their full combined aesthetic effect as one does in a mosque or madrasa, but one is able to pay them a different attention.

At the Institut du Monde Arabe, meanwhile, there is a show on contemporary Morocco and a full calendar of events. It is a little strange to open a show on contemporary Moroccan art with a film that is already 15 years old, but “Le Mur” by Faouzi Bensaidi is a gem. The short film takes place against a tightly framed white wall — we never see beyond its edges. Bensaidi stages a whirlwind of deft vignettes: a man chases his girlfriend to a car, another throws a rock at his lover’s window, a thief clambers down, two boys get yelled at for drawing dirty pictures, a wounded man drags himself along, leaving a trail of blood. In the dark of night, workers rush to whitewash all the traces of conflict away. In the last frame, a schoolboy nonchalantly scrawls on the freshly painted wall on his way to school. It is a brilliant depiction of society as constraint and support, a barrier we hardly notice, so busy are we figuring out how to circumvent, play along and make use of it.

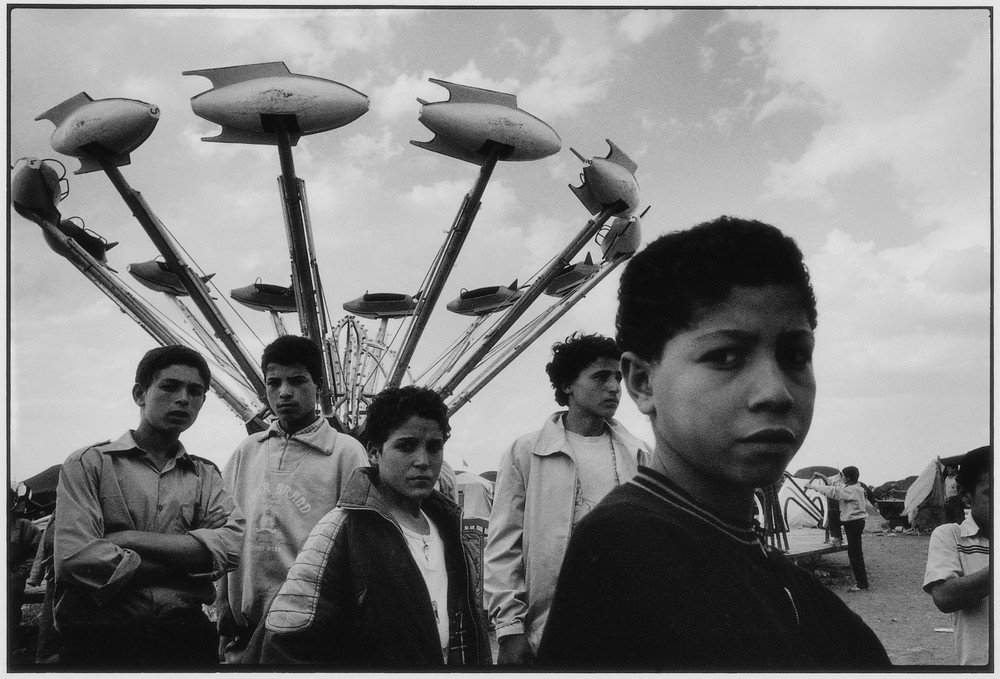

I also liked the black and white photographs that make up Hesham Benohoud’s “The Classroom” series, in which Moroccan school children are posed floating in various states of surreal alienation or disembodiment.

At the opening of this show, Prime Minister Francois Hollande emphasized that France and Morocco “need each other.” Relations between them are strained at the moment. Last February a French judge investigating allegations of torture called in for questioning the head of Morocco’s secret services, Abdelatif Hammouchi, who was passing through Paris. Mr. Hammouchi did not appear and Morocco suspended judicial cooperation with France. That same month, the Spanish actor Javier Bardem — a supporter of Western Sahara’s independence — claimed that a French ambassador had described Morocco to him as “a mistress that one sleeps with every night, that one doesn’t particularly love, but that one must stand up for.”

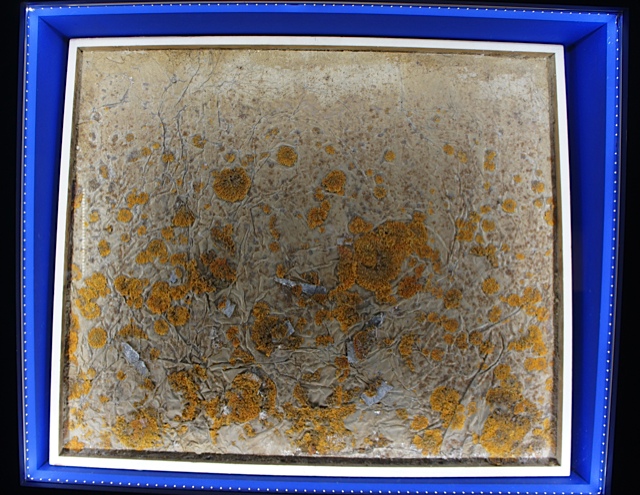

The shows in Paris have been viewed as partly an attempt to patch things up. The one at the Institut du Monde Arabe has a slap-dash quality that makes one wonder if it wasn’t thrown together, or expanded, at the last minute. It features pioneering 1960s artists of great significance such as Farid Belkahia — who painted on animal skin, with vegetable pigments, and gave his canvases organic shapes — and iconoclasts like El Khalil El Ghrib, who makes strange patient decaying concoctions of found materials — stone and wood and moss and wire and fabric — that mesmerize with the blurred traces of the creator’s intention. You can catch a glimpse of his spectacularly messy studio and hear him talk (in French) with charming earnestness about his decision not to sell his work here.

They are exhibited alongside younger artists of quite variable talent. Some of the work is great but plenty of it is immature, or heavy-handed. I thought there was a dearth of accompanying texts. Instead, staff from the Institut circulates among the crowd, repeating short memorized explanations of the pieces. The themes (Sufism, women and their bodies, religion) are rather obvious, and the show fizzles out into a strange folkloric/commercial coda, with kaftans and carpets suddenly featured at the end.

The show in Paris should travel to Morocco next, and be hosted at the new Mohamed V Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. At the top of the main avenue in downtown Rabat, the two-story white building — decorated with white mashrabeya and a silver cornice — is architecturally subdued, more concerned with fitting in than making a statement. Inside, the building still has that slightly stage-set quality of so many cultural institutions in the region — as if they’re not quite sure who, besides the dignitaries at the opening ceremony, will show up, or if they want anyone to. No café or gift shop yet, and the shelves of the information booth are quite empty. But the staff are eager, and there were quite a few visitors on the week day I went; the museum says there have been over 30,000 since it opened.

What is strangest about the museum is that the visit is in reverse-chronological oder, starting with the work of contemporary young artists and ending with Mohammed Ben Ali R’bati, considered the country’s first modern painter.

This potentially interesting conceit ends up being confusing, especially as each artistic era is explained largely as a reaction to preceding historical events, artistic schools and tendencies. These includes the rejection of early Orientalist and naif art; the reaction to Western aesthetic influences and political domination; debates over building a new national art versus valorizing individual experience and expression, and pure versus expressionist abstraction, which went on for decades.

Having only seen one room of younger artists, I thought the contemporary art was given very short shrift. But I’ve since discovered that a bunch of it is being housed in the basement, a choice that speaks loudly of established hierarchies (and “underground” status). Very much looking forward to going back and seeing the rest.