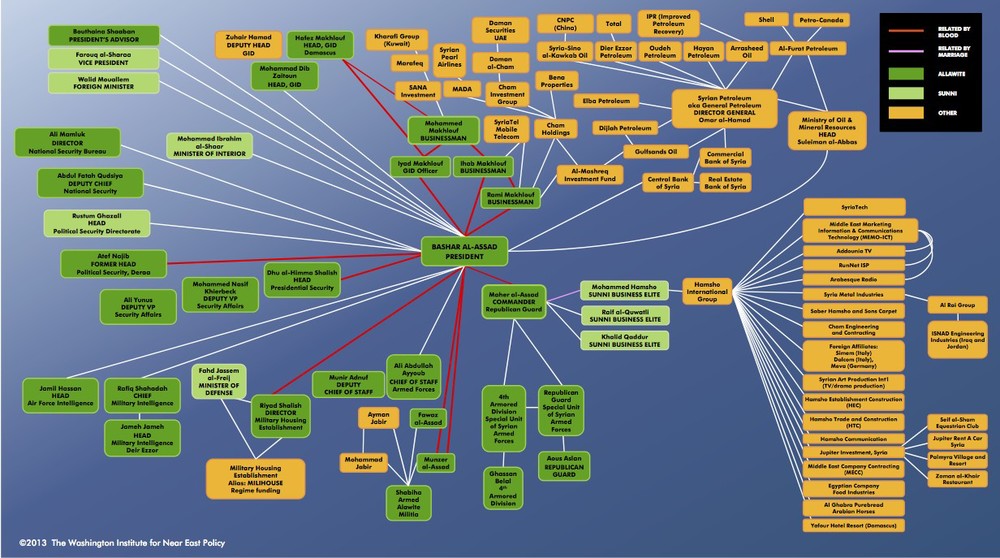

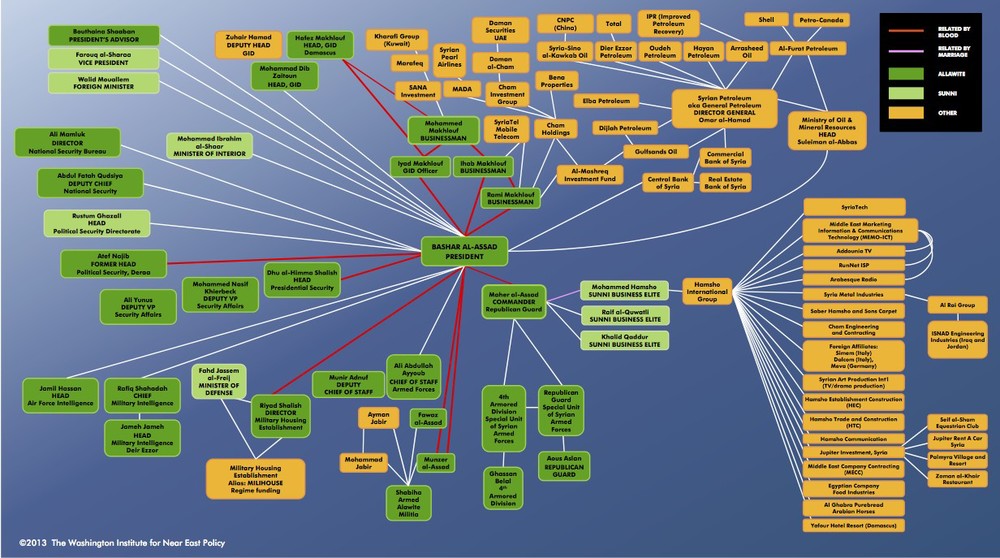

An interesting chart of Syrian regime figures and institutions, by WINEP.

An interesting chart of Syrian regime figures and institutions, by WINEP.

From the Arab West Report’s newsletter, by its editor Cornelis Hulsman, a veteran advocate of better Muslim-Christian relations in Egypt who has extensive contacts on both sides:

The Kerdassa police station (Giza) has been attacked using an RPG after elsewhere in the city sit-ins of demonstrators were broken up. This resulted in the death of the local police chief and several police officers whose bodies have then be mutilated. Twenty other police stations were attacked, often with weapons that they were not prepared for. Demonstrators who claimed to be with the Muslim Brotherhood threw a police car with 5 policemen from a bridge killing all of them. Those images are spread all over and have created a shock-wave. It is thus no wonder that policemen seek safer locations to operate from. It also makes the mutual hate between police and Muslim Brothers and militant groups much deeper. The mutual hate is many decades old. Between 1992 and 1997 militant Muslims engaged in attacks on police and civilians. Militant Muslims and political Islamists were targeted by police, many of them ended up for years in prison, also if they had no involvement with any violence. The police did not have a good reputation. Officers were often accused of torture. It is thus no wonder that the police are most hated by Islamists and now, just as on January 28, 2011 and following weeks, are targeted.

The patterns of systematic attack on Egyptian security resemble those of January 28, 2011. People have again come from villages and popular areas to massively destroy government property. But unlike 2011, people now also targeted churches and Christian shops. AWR called priests, friends of ours, in Beni Suef, Fayoum, Maghagha, and Minya. The police have disappeared from all these cities and other cities because they became targets themselves and fled. That is no wonder if one sees on videos how policemen have been brutally slaughtered in Cairo and other parts of Egypt. The consequence is that the police are withdrawing to centers where they feel safe and can defend themselves better. The consequence, however, is that thugs have had more opportunities to engage in violence and destruction. The police in Assiut disappeared on the 14th from the street, but returned again on the 15th.

Violence is widespread, but AWR has also spoken with priests who told us that there had been no violence in their village or town. Much of this also, but not only, depends on local relations. Fear is widespread in all parts of Egypt. If particular areas have not yet been targeted they later may or may not become targets.

It all appears that General al-Sisi has made a miscalculation when he, in cooperation with other authorities, decided to end the demonstrations around the Rābaʽah al-‘Adawīyyah mosque and al-Nahda square. Protesters spread and throughout the country militant groups are seen. It is obvious that these groups are organized. It is not possible to explain how otherwise they suddenly appear all over Egypt. AWR has asked friends in various cities to explain why they believe that these were Muslim Brothers. Some friends said that the people marching with weapons in the streets scream, “Islamiya, Islamiya.” Many of them are young. They were surprised to see also small children among them. Priests we spoke to said they believed them to be a mix of Brothers joined by many thugs, people seeing an opportunity to loot.

Emad Aouni lives in Assiut and has seen Muslim Brothers he knows from the sit-in in Assiut participating in attacking churches. They were, however, not alone but in the company of members of the Jamā’ah al-Islāmīyah, Salafīs, and thugs. “They usually would not do this alone but in a group with other Islamists they would go along.”

AWR’s website has been hacked, so the full piece is not up there. I am pasting it here for those who are curious – it also includes a full list of churches that have come under attack.

Adam Shatz in the LRB:

So this is how it ends: with the army killing more than 600 protesters, and injuring thousands of others, in the name of restoring order and defeating ‘terrorism’. The victims are Muslim Brothers and other supporters of the deposed president Mohammed Morsi, but the ultimate target of the massacres of 14 August is civilian rule. Cairo, the capital of revolutionary hope two years ago, is now its burial ground.

Particularly harsh words for the revolutionary camp:

The triumph of the counter-revolution has been obvious for a while, but most of Egypt’s revolutionaries preferred to deny it, and some actively colluded in the process, telling themselves that they were allying themselves with the army only in order to defend the revolution. Al-Sisi was only too happy to flatter them in this self-perception, as he prepared to make his move. He, too, styles himself a defender of the revolution

James Traub in Foreign Policy argues that “what happened in Egypt was not a second ‘revolution’ against authoritarian rule but a mass repudiation of Muslim Brotherhood rule.” He also looks at the intellectual and moral obfuscation that most of the country’s “liberals” are engaged in regarding their support for the military coup.

Morsy’s single greatest mistake, in retrospect, was failing to put [many Egyptians’] fears to rest by ruling with the forces he had politically defeated. He was a bad president, and an increasingly unpopular one. But nations with no historical experience of democracy do not usually get an effective or liberal-minded ruler the first time around. Elections give citizens a chance to try again. With a little bit of patience, the opposition could have defeated Morsy peacefully. Instead, by colluding in the banishment of the Brotherhood from political life, they are about to replace one tyranny of the majority with another. And since many Islamists, now profoundly embittered, will not accept that new rule, the new tyranny of the majority will have to be more brutally enforced than the old one.

Brian Whitaker, writing in The Guardian :

Viewed from Washington, Yemen is not a real place where people are demanding social justice and democracy so much as a theatre of operations in Saudi Arabia’s backyard, veteran Yemen-watcher Sheila Carapico told a conference in January.

In fact, she added, the US doesn’t really have a policy on Yemen. What it has instead is a longstanding commitment to the security and stability of Saudi Arabia and the GCC states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates), coupled with an anti-terrorism policy in which Yemen is treated as an extension of the Afghan/Pakistani theatre. The result, she said, is “pretty much the antithesis” of what Yemenis were aspiring to when they set about overthrowing President Saleh in 2011.

From Gallup, data on Egyptian perceptions of well-being in the last eight years. When 1/3 of your population feels it is “suffering” you have a big problem on your hands.

Remember this headline, in the state-owned newspaper of a supposedly secular, US-friendly regime run by a military that receives $1.3bn in US aid per year. Via:

“Egypt rejects the exhortations of the American Satan” says headline in state newspaper Al-Akhbar (egy, not iranian) pic.twitter.com/oRRcn88jZ8

— Samer Al-Atrush (@SameralAtrush) August 8, 2013

And while we’re at it:

Akhbar reports “judicial sources” saying evidence US embassy participated in killing protesters in Jan 25

— Samer Al-Atrush (@SameralAtrush) August 8, 2013

ICG’s new report out on Egypt:

Nearly two-and-half years after Hosni Mubarak’s overthrow, Egypt is embarking on a transition in many ways disturbingly like the one it just experienced – only with different actors at the helm and far more fraught and violent. Polarisation between supporters and opponents of ousted President Mohamed Morsi is such that one can only fear more bloodshed; the military appears convinced it has a mandate to suppress demonstrators; the Muslim Brotherhood, aggrieved by what it sees as the unlawful overturn of its democratic mandate, seems persuaded it can recover by holding firm. A priority is to lower flames by releasing political prisoners – beginning with Morsi; respect speech and assembly rights; independently investigate killings; and for, all sides, avoid violence and provocation. This could pave the way for what has been missing since 2011: negotiating basic rules first, not rushing through divisive transition plans. An inclusive reconciliation process – notably of the Brotherhood and other Islamists – needs more than lip-service. It is a necessity for which the international community should press.

Despite sound advice not to, some Egyptian officials and Tamarod activists are persisting in comparing the ousted Muslim Brotherhood president Mohammed Morsi to Adolf Hitler, the key variable being that they both came to power through democratic means. An actual comparison to the two leaders is kind of interesting, but to those who say Morsi could have turned out like Hitler had he not been toppled, I would say: This analogy does not offer the lesson that you think it offers.

Corrollaries of Godwin’s Law notwithstanding, there are times when it’s useful to invoke Hitler. Let’s say, for example, that your argument partner says it’s impossible for an dog lover to be cruel to humans. Well no, you’d say, Hitler loved dogs. But if you try to make the opposite argument — that there’s something wrong with liking dogs because Hitler was a dog lover — then you should face all the scorn that the Internet can muster.

Logically, the Morsi-as-Hitler arguments pass this test. They don’t say that all leaders who come to power through democratic means are likely to turn out to be Hitler, merely that it’s possible — and thus, a coup to overthrow them is not always going to be a bad thing. It’s in terms of historical prediction, that Morsi was actually likely to turn out like Hitler, that the comparisons fall flat on their face.

Firstly, to clear one thing up, Hitler was not elected. He was chosen as Chancellor (roughly, the prime minister) by the elderly President Paul von Hindenburg on the urging of the failed conservative ex-chancellor Franz von Papen. The Nazis, the largest party in parliament, had a claim on the right to try to form a government.

But here the analogy breaks down. Von Hindenburg was a field marshal, and von Papen a monarchist with ties to the aristocracy, and together they represented that segment of the German state and elite — in particular the officer corps — that was heartily sick of democracy. Most of them hated the Weimar republic’s political chaos, despised pluralism, feared the window that democracy gave to Communists, and generally looked back to the good old days of the Kaiser. The Nazis made quite clear that they intended to abolish Weimar pluralism and the elite was all for it. “If Hitler wants to establish a dictatorship, the Army will be a dictatorship within the dictatorship,” Defense Minister Kurt von Schleicher is reported to have said.

This is important because it explains what Hitler was able to do once he became Chancellor in January 1933. Von Hindenburg essentially abolished civil liberties via the Reichstag Fire Decree — presented as a response to a Communist revolutionary plot. Hitler used that to ban the Communists, arrest much of the remaining opposition, bully the remainder of parliament into making him de facto dictator via the Enabling Act, then complete his suppression of the opposition. All this happened within six months of Hitler taking office. The conservative elite, the armed forces, the police, and much of the non-Nazi public went along with him every step of the way. By mid-1933, Germans were legally required to salute each other in the street with a rousing “Heil Hitler.” (A lot of individuals instrumental in Hitler’s rise who had the idea that they could control the Nazi leader fell out with him — von Schleicher and von Papen, for example — but Hitler continued to court the institutions and the institutions continued to back him.)

We may compare this to Morsi’s Egypt. By September 2012, Freedom and Justice party officers were regularly being torched across the country, and the police were openly indicating that they weren’t going to protect them. Marx’s tragedy/farce quip is overused but it applies spot-on to Morsi’s version of the Enabling Act, the November 2012 Constitutional Decree, in which the Egyptian president granted himself far-reaching powers over a state that basically ignored him, and ended up having to flee his own presidential palace and withdraw his decree within two weeks. (It’s also highly questionable whether Morsi intended the Constitutional Decree as anything more than a short-term measure to push through a flawed, but still basically pluralist and democratic constitution.)

There are a number of other factors that differentiate Egypt from Germany — it had just gone through the triple trauma of World War I, hyperinflation, and global depression. (For anyone inclined to mention the Egyptian pound dipping to seven to the dollar, this is what a billion-mark banknote looks like). Any account of Hitler’s rise to power must also take into account his astounding abilities as a public speaker.

But, the difference that speaks the most to Egypt’s current experience is that German state institutions were on board with Hitler’s plan to abolish pluralism and the separation of powers. It’s worrisome when a leader doesn’t respect democratic principles, but it’s a lot more worrisome when the state, and especially the armed forces, don’t do so.

To go back to the beginning, and the appropriate use of historical analogy, the experience of Germany in the 1930s does mean that you have to have the cooperation of state institutions to stomp out the opposition. Sometimes, the army collapses due to internal mutinies, the officer corps is swept away, and the new regime can create new armed forces like Red or Revolutionary Guards that are steeped in its ideology — as in Russia in 1917, or Iran in 1979. Such mutinies frequently happen when groups of conscripts are ordered by officers to fire into crowds. This is another thing for Egypt to keep in mind.

Eurasia’s Ian Bremmer thinks so, saying SCAF’s challenge is to rig the appearance of a civilian government just right :

Today, the main difference with Pakistan’s military is that Egypt’s is now seen as responsible for the day-to-day functioning of governance. The generals will once again go for the Goldilocks approach to forming a civilian government, one that is not too strong but not too weak. It has to be resolute enough to earn a reputation for competence (this is where Mursi and the Muslim Brotherhood fell short), but docile enough to not sideline the military or curb its privileges. Most importantly, the new government needs to seem sufficiently independent to take flak and “own” the blame for any economic woes. The last thing the military wants is for the next wave of protestors to aim their anger at the army.

Can the military pull this off? Can it empower a government that earns enough public confidence to restore stability to the country and allows the military to distance itself from economic management and domestic politics?